3-8

Maneuvering Techniques

Steering response depends on three factors: engine position, motion and throttle.

Like an automobile, high speed

maneuvering is relatively easy and

takes little practice to learn. Slow

speed maneuvering, on the other

hand, is far more difficult and

requires time and practice to master.

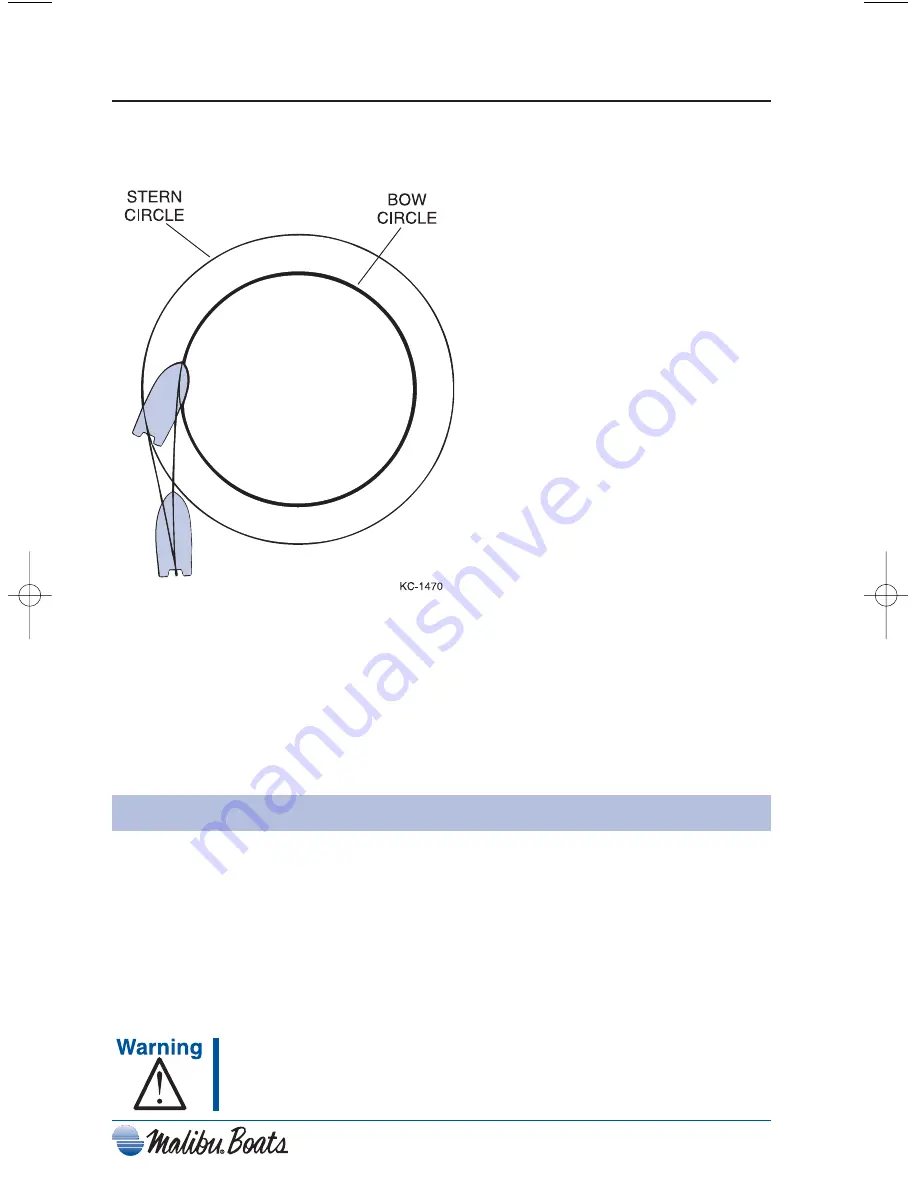

When making tight maneuvers, it is

important to understand the effects of

turning. Since both thrust and

steering are at the stern of the boat,

the stern will push away from the

direction of the turn. The bow

follows a smaller turning circle than

the stern.

The effects of unequal propeller

thrust, wind, and current must also be

kept in mind. While wind and current

may not always be present, an

experienced boater will use them to

his advantage. Unequal thrust is an

aspect shared by all single engine propeller-driven watercraft. A clockwise rotation

propeller tends to cause the boat, steering in the straight ahead position, to drift to

starboard when going forward, and to port when going backward. At high speed, this

effect is usually unnoticed, but at slow speed; especially during backing, it can be

powerful. For this reason, many veteran boaters approach the dock with the port side of

the boat toward the dock, if possible.

Stopping

When stopping the boat, it is important to remember there are no brakes to allow coming

to a complete, immediate stop. To stop your boat, anticipate ahead of time and begin

slowing down by pulling back on the throttle.

Once the throttle is in neutral and the engine has stopped pulling the boat forward, it may

be necessary to pull the throttle into reverse to further slow the forward momentum of the

boat. The reverse thrust of the engine will decrease the forward speed and slow the boat

down to a safer maneuvering speed.

Do not use the engine stop switch for normal shut down.

Doing so may impair your ability to re-start the engine quickly

or may create a hazardous swamping condition.

Figure 3-8. Stern Push

Chapter 3 doc.qxd 8/17/04 3:10 PM Page 8