11

through the telescope. Avoid viewing over rooftops and chimneys,

as they often have warm air currents rising from them. Similarly,

avoid observing from indoors through an open (or closed) win-

dow, because the temperature difference between the indoor

and outdoor air will cause image blurring and distortion.

If at all possible, escape the light-polluted city sky and head for

darker country skies. You’ll be amazed at how many more stars

and deep-sky objects are visible in a dark sky!

“Seeing” and Transparency

Atmospheric conditions vary significantly from night to night.

“Seeing” refers to the steadiness of the Earth’s atmosphere at

a given time. In conditions of poor seeing, atmospheric turbu-

lence causes objects viewed through the telescope to “boil.”

If you look up at the sky and stars are twinkling noticeably,

the seeing is poor and you will be limited to viewing at lower

magnifications. At higher magnifications, images will not focus

clearly. Fine details on the planets and Moon will likely not be

visible.

In conditions of good seeing, star twinkling is minimal and

images appear steady in the eyepiece. Seeing is best over-

head, worst at the horizon. Also, seeing generally gets better

after midnight, when much of the heat absorbed by the Earth

during the day has radiated off into space.

Especially important for observing faint objects is good “trans-

parency”—air free of moisture, smoke, and dust. All tend to scat-

ter light, which reduces an object’s brightness. Transparency is

judged by the magnitude of the faintest stars you can see with

the unaided eye (5th or 6th magnitude is desirable).

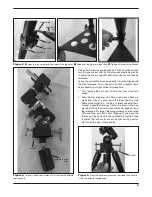

Star-Testing the Telescope

When it is dark, point the telescope at a bright star and accu-

rately center it in the eyepiece’s field of view. Slowly de-focus the

image with the focus knob. If the telescope’s optics are correctly

aligned, the expanding disk should be a perfect circle

(Figure

16). If the image is unsymmetrical, the optics are out of align-

ment. The dark shadow cast by the secondary mirror should

appear in the very center of the out-of-focus circle, like the hole

in a donut. If the “hole” appears off-center, the optics are out of

alignment.

If you try the star test and the bright star you have selected

is not accurately centered in the eyepiece, the telescope will

appear to need collimating, even though the optics may be

perfectly aligned. It is critical to keep the star centered, so over

time you will need to make slight corrections to the telescope’s

position in order to account for the sky’s apparent motion.

given time. In conditions of poor seeing, atmospheric turbulence

causes objects viewed through the telescope to “boil.” If you look

up at the sky and stars are twinkling noticeably, the seeing is

poor and you will be limited to viewing at lower magnifications. At

higher magnifications, images will not focus clearly. Fine details

on the planets and Moon will likely not be visible.

In conditions of good seeing, star twinkling is minimal and

images appear steady in the eyepiece. Seeing is best overhead,

worst at the horizon. Also, seeing generally gets better after mid-

night, when much of the heat absorbed by the Earth during the

day has radiated off into space.

Especially important for observing faint objects is good “trans-

parency”—air free of moisture, smoke, and dust. All tend to scat-

ter light, which reduces an object’s brightness. Transparency is

judged by the magnitude of the faintest stars you can see with

the unaided eye (5th or 6th magnitude is desirable).

Cooling the Telescope

All optical instruments need time to reach “thermal equilibri-

um.” The bigger the instrument and the larger the temperature

change, the more time is needed. Allow at least 30 minutes for

your telescope to acclimate to the temperature outdoors before

you start observing with it.

Let Your Eyes Dark-Adapt

Don’t expect to go from a lighted house into the darkness of the

outdoors at night and immediately see faint nebulas, galaxies,

and star clusters—or even very many stars, for that matter. Your

eyes take about 30 minutes to reach perhaps 80% of their full

dark-adapted sensitivity. As your eyes become dark-adapted,

more stars will glimmer into view and you’ll be able to see fainter

details in objects you view in your telescope.

To see what you’re doing in the darkness, use a red-filtered flash-

light rather than a white light. Red light does not spoil your eyes’

dark adaptation like white light does. A flashlight with a red LED

light is ideal. Beware, too, that nearby porch, streetlights, and car

headlights will ruin your night vision.

Eyepiece Selection

Magnification, or power, is determined by the focal length of

the telescope and the focal length of the eyepiece being used.

Therefore, by using eyepieces of different focal lengths, the

resultant magnification can be varied. It is quite common for

an observer to own five or more eyepieces to access a wide

range of magnifications. This allows the observer to choose the

best eyepiece to use depending on the object being viewed

and viewing conditions. Your BX90’s EQ refractor comes with

25mm and 10mm eyepieces, which will suffice nicely to begin

with. You can purchase additional eyepieces later if you wish to

have more magnification options.

Magnification is calculated as follows:

Telescope Focal Length (mm)

= Magnification

Eyepiece Focal Length (mm)

For example, the BX90 EQ has a focal length of 600mm, which

when used with the supplied 25mm eyepiece yields:

600 mm

= 24x

25 mm

The magnification provided by the 10mm eyepiece is:

600 mm

= 60x

10 mm

The maximum attainable magnification for a telescope is directly

related to how much light it can gather. The larger the aperture,

Summary of Contents for 52588

Page 3: ...3 Figure 1 Parts of the BX90 EQ refractor A H I J F G C D B L K M E...

Page 14: ...14...

Page 15: ...15...